I’ve often called research the equivalent of the scene in the Wizard of Oz where Dorothy and friends are quaking in their ruby slippers at the booming voice and larger than life head of the Great and Powerful Wizard of Oz, only to find, thanks to Toto’s curtain-revealing revelation that the powerful Wizard is just an ordinary man.

I’ve often called research the equivalent of the scene in the Wizard of Oz where Dorothy and friends are quaking in their ruby slippers at the booming voice and larger than life head of the Great and Powerful Wizard of Oz, only to find, thanks to Toto’s curtain-revealing revelation that the powerful Wizard is just an ordinary man.

Last week, a story was published in Psychology Today by Santoshi Kanazawa, faculty at the London School of Economics, that claimed there was objective evidence that African American women are less attractive than women of other racial and ethnic backgrounds (the original article was pulled, but you can find it here). The so-called evidence for this “finding” was, as it turns out, not objective at all. In fact, the author of the study, known for his provocative research and articles, used a data set in which the “data” about the attractiveness of African American women was based on researcher observations and ratings of the sample – in other words, it wasn’t the sample that was asked to measure attractiveness, it was the researchers who rated the sample themselves (in this case, participants in a longitudinal study that followed participants from adolescence to young adulthood).

The data Kanazawa used and obscurely referred to was taken from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health (Add Health Study). The Add Health study does not survey how American adolescents define or measure attractiveness. Rather, Kanazawa used the data in which researchers themselves “objectively” measured the participant’s attractiveness.

What? First of all, why would this have been measured in the first place? What did the so-called attractiveness of each adolescent involved in the study have to do with their health? Second, how could the rating be measured “objectively?” What criteria was used? And how was the instrument (if any) validated? How can any scientist consider rating attractiveness “objective?” We don’t and won’t know because Kanazawa fails to provide any of that information in his article. Additionally, that information was never presented as relevant to the study. Because it isn’t relevant to the Add Health study (here is a great response to Kanazawa’s “science” by Khadijah Britton at the Scientific America blog). Why this measurement of participant attractiveness was even done in the first place is questionable. It’s only relevant because Kanazawa wants the general public to believe that there is “objective scientific evidence” that African American women are less attractive. Which may actually be more evident of the researchers attempt at confirmation bias than true, objective scientific research.

There are several problems here, of course one being the highly racialized and racist nature of these types of studies that pretend to use objective evidence but in fact are totally based on subjective measures that are situated in the cultural contexts of the researcher. Second is the problem of social scientists in trying to prove objectivity in the subjective.

I thought this quote by George Michaelson Foy in his response at Psychology Today laid it out nicely:

“Maybe the key issue here is this: social scientists should come to terms with the extraordinary nature of their subject matter. It is a much, much harder job to figure out a tiny percentage of how the human mind works than it is to send a space vehicle to Mars…As a general rule, the tools and equations of physics do not work on the human mind.”

A lot of the buzz I saw on the internets focused on the above issue. But I was really pleased to see this piece by Latoya Peterson at Racialicious. Latoya breaks it down well: who is the researcher in question, what is the researcher’s position and agenda (because contrary to popular belief, a researcher does NOT leave the collective collage of experiences, frameworks, biases and beliefs at the door), what is the methodology and, my favorite point, be wary of people trying to quantify what is subjective.

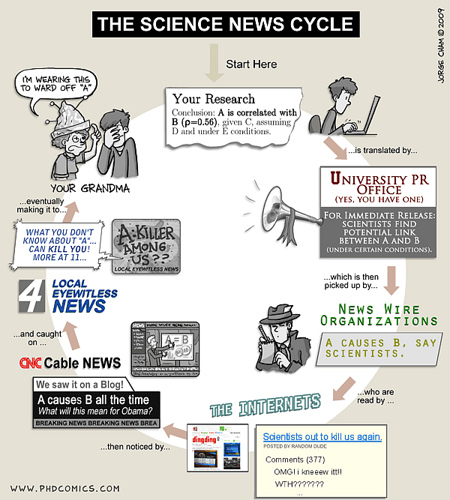

But the sketchy, racist research is only part of the problem. There are a few other issues that warrant further discussion. Latoya’s post at Racialicious included one of my favorite cartoons, by Jorge Cham, creator of PhD Comics: Piled Higher and Deeper.

I love this particular comic. Back in February of this month, I came across this headline that caused me to send an email with the link to all my colleagues at the Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare. The headline – No racial bias at child protective services: study with the tagline, “Child abuse really is more common in African American than white homes, according to a new study that dismisses earlier claims of racial reporting bias in the child welfare system.” The article by Drake et. al. the news report was based on did not discount racial bias as the reason for disproportionality in its entirety, but rather found a correlation (not to be confused with causation) between risk factors (including poverty) in African American communities and reports of abuse and neglect.

Part of being a good consumer of research is looking at the study carefully for all the elements and understanding what those elements mean. For example, very few studies can be considered representative. The sample size must be very large in order for the researcher to claim that the population being studied is even a wee bit similar to the overall population. Most research studies rely on smaller samples, and therefore the study can only say X has a relationship to Y in this particular sample. Many consumers of media are also less aware that research studies like the Drake et. al article use proxy measurements for things that cannot be directly measured. For example one of the problems I had with the Drake et al study is that they only looked at infant mortality rates as a comparison which I think is limited. The goal of the article as I interpreted it was to encourage child welfare agencies and other agencies that work with families to address the larger macro issues around child well being, and to work to address the factors that may lead to African American children’s risk of abuse and/or neglect. However, the Reuter’s headline was misleading and only served to “blame the victims” of racial inequality – much as the Cham comic illustrates. The media is just as much at fault here, for the way they soundbite research – as are organizations such as Psychology Today that publish articles that are more opinion than science.

I was going to include my thoughts about the book I just finished this week, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Sloot, because this book heavily features the ethics of research but I think I’ll save that part for my next post. The point I’m trying to make is threefold: first, that researchers are all just ordinary people, not Great and Powerful Wizards of Oz’s. Everything we bring to the research “lab” and no matter what we are studying – cells, mice, or humans – is situated in the researcher’s social and cultural context: where the researcher was born, raised, educated; what the researcher experienced and learned, the tools and measurements that have been used, the questions that motivate the research topic and inquiry itself. We cannot fully bracket out how each of us as researchers see the world, we can only acknowledge that we have those experiences and frameworks and choose to address them as ethically and responsibly as possible.

Second, as Latoya mentions in her piece, we need to ask questions whenever research attempts to quantify the subjective. Just because a couple of researchers rated African American female study participants “less attractive” and put a number on it does not mean anything more than that a couple of researchers put a number on something as subjective as “attractiveness.” Is a number a fact or is it a proxy for something else? A number means nothing unless there are other numbers within socially constructed meanings around it that give it its context.

Third, we must critically think about what is studied and why. Social science research can validate or it can marginalize people. Sometimes research can help people realize that their human experience is shared by others; on the other hand, in an effort to try to “understand” humanity research often falls victim to trying to quantify a “norm” which often ends up reinforcing the marginalization of those who are already oppressed. There is so much diversity of experiences and cultural contexts, even within a country such as the United States, that I question whenever a researcher attempts to find an “average” or “normal” anything.

And finally we need to remember that this goes back again to the person doing the research. Just because Kanazawa and others know how to push our buttons and levers in the Wizard booth does not make them Great nor Powerful. We can all learn to be Toto, revealing the mere human behind the lighting and sound effects. Don’t let pretty graphs and charts distract you from the man behind the curtain.

Great post. In a much less evidence-based and thoughtful way, I cynically imagine that you can find or make research back up just about any claim you want to make – whether it’s by having a limited sample base or just by extrapolating loads of theories out of limited evidence. For me, this is why it is so important when looking at research to look at and understand the methodology rather than just read the headline.